Meditation As The Still Point

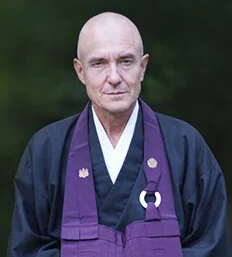

Ryushin Marchaj, Sensei, is a priest in the tradition of Zen Buddhism. Leaving his career as a pediatrician and psychiatrist, he entered into full-time residence at the Zen Mountain Monastery in 1992 and served as abbot from 2009 to 2015.

Ryushin has been leading intensive workshops for the cancer patients, survivors and their family members since 2016. In this brief interview, he sheds light on the practice of mindfulness and the connection between meditation and creativity.

What inspired you to create a meditation workshop specifically for those who lives have been impacted by cancer?

I was inspired by Theatre Within Artistic Director, Joe Raiola, who came to me with the idea. There are not too many things I feel qualified to share with people. Meditation is one of them. If someone is interested in investigating the nature of their experience and seeking intimacy with all dimensions of their lives and with others, I am hard pressed not to get enthusiastic and start behaving like a used car salesman. Although I feel confident that what I am sharing is actually a decent vehicle. And as much as there is something very compelling and nurturing to be with people who are navigating their illness, and their wholeness while living and possibly dying, I believe that meditation as an exhaustive and wholehearted act of inquiry, intimacy, lovingkindness and equanimity, remains relevant to everybody at any stage of their life.

You have said that teaching this workshop at Gilda’s Club is “essential.” In what sense do you mean that?

It is essential because to be awake is essential, especially when what we are facing is challenging and we are programmed to get distracted in those moments. And being distracted, we miss the opportunities that are presenting themselves, most importantly opportunities to give and receive some loving. It is essential because without attending to details of our lives, without exercising the gift and the power of our mindfulness, we die well before we actually are found by our death.

Both as a pediatric physician and monastic you have been close with many people, including your Dharma teacher, John Daido Loori, in the final stages of their lives. What did you learn from that experience?

To not turn away, both in terms of my actual gaze and the way I look and see what is unfolding in front of me, especially when things get painful, and to not turn away my heart, my capacity to feel. It really is about refining our ability to be completely present, and if we are to be helpful or to receive help, to let that emerge from the clarity which is the presence of our eyes and heart.

Can we really get past our fear of death or is it intrinsic?

There is nothing that is intrinsic. That would subvert the truth of impermanence. So, yes, it is possible to live one’s life free of fear, including the fear of death. When we realize directly that the self is not intrinsic, the nature of death is illuminated in a radically new way.

How does meditation relate to creativity?

Meditation reveals the continuous and instantaneous creative nature of our minds. In a sense, there is nothing but creativity, given that there is nothing that persists for longer than a moment, given that even the existence of this moment is somewhat suspect. From a slightly less extreme perspective, meditation presents us with our habit patterns, conditioning that we cling to in order to attempt to secure ourselves in a set of givens. Within those givens, we try to freeze reality into predictable units. Meditation melts these illusions, revealing the kaleidoscopic and ceaselessly creative aspect of life.

In “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which was inspired by the Tibetan Book of the Dead, John Lennon sings, “Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void, it is shining,” and “Love is all and love is everyone, it is knowing.” Does surrender in the sense that Lennon wrote about lead to the discovery/realization of infinite love?

It is always tricky and bit presumptuous to imagine that I would know what anybody meant when they said anything. I rather try to figure out what I mean when I say something. Too frequently we are overtly or implicitly aggressive in how we relate with reality, even when we engage deliberate spiritual approaches and methods. We know how to advance. We know how to claim territory, even if it is the territory of insights into selfless truths. We are amazingly skillful in keeping the idea of the self in the picture and let that self terrorize reality through anger and greed and basic dullness. “Laying down thoughts” is a good starting point, and becoming fascinated with what is revealed afterwards. It may be love or light or even knowing love and light. But a song can as easily become dogma as a religious scripture. And I am certain that both the Tibetans who wrote the book and Lennon would not care that we were humming these words under our breaths, but that we saw them as an invitation to consider something with passion, consider what this life really is.